Ashley Smith looks at the current climate and the importance of good credit management.

‘Corporate responsibility’ is currently high on board room agendas as the press follows the global recession, so now is an ideal time for companies to consider their payment terms and the resultant effect of their policies on their supply chain.

We have recently seen Argos, Dell and Unilever announce increases in payment terms to their suppliers to 90 days yet these same companies apply very different terms to their own customers. Non-account Argos customers are expected to pay at the time of order whilst trade customers are extended 28 days credit. Unilever has issued a statement attempting to justify their decision: “By working with suppliers to release cash, we provide funds for Unilever to invest in further growth, which is in the long-term interests of us and our suppliers.”

But consider the reality of this statement, it’s far cheaper to obtain funding from suppliers than it is from banks and Purchasers more often than not can ignore suppliers terms whilst they can’t ignore their banks covenants.

If a large Company breaches its covenants with its bank or fails to make a payment or bounces a cheque, the bank will charge up to £25 per letter and in extreme cases can call in its loans to the Company. For the bank this is easy, it simply deducts charges and interest from the Companies account at the time of issue.

In the alternative if a supplier to the same Company provides finance through Trade Credit and the purchasing Company breaches its payment terms - and the supplier complains and raises Statutory Late Payment charges plus interest - the purchaser can simply switch suppliers at no cost. If the Supplier is however able to issue charges and interest he may still have to incur additional costs in collection and litigation as many Large Companies may simply refuse to pay the Late Payment Charges.

The 2000/35/EC’19 Directive should prohibit the abuse of freedom of contract to the disadvantage of the creditor. When an agreement mainly serves the purpose of procuring the debtor additional liquidity at the expense of the creditor, or where the main contractor imposes on his suppliers and subcontractors terms of payment which are not justified on the grounds of the terms available, these may be considered to be factors constituting such abuse.

The Directive proposes to address this issue by a) tightening the rules on grossly unfair contracts and b) allowing SME’s to charge for full recovery costs.

On the other side of the coin, McDonald's is an example of a company using the latest technology to ensure that its supply chain is kept fully up to date with the progress of an invoice through its systems by using an Online Accounting System to which all suppliers have access. A supplier can check that an invoice is logged, check the payment date and review any comments made by McDonald’s staff during the payment process. This enables queries to be dealt with within the payment terms and gives the supplier the safe knowledge that McDonald’s will make payments in accordance with the agreed credit terms.

Considering the effects of payment terms on the working capital of a business, in essence, a business must deal with three main aspects of its accounting: prepayments, wages and credit. The success or failure of a business in terms of cash flow is how a business juggles and offsets the plus and minus of these three core elements.

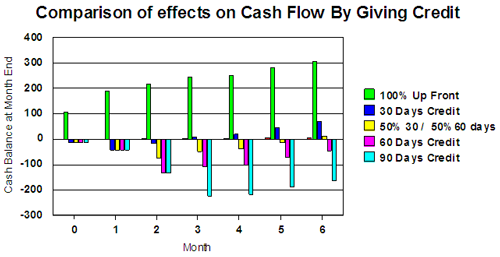

So lets look at five different business all starting on 31st December. For argument’s sake, all transactions take place on the last day of the month, every business has identical sales of £100,000 per month and an identical overhead structure making £20,000 per month pre-interest and tax profits.

| Summary | |||||||

| Cash Balance at month End £'000 | |||||||

| Month | |||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 100% Up Front | 106 | 192 | 219 | 246 | 253 | 280 | 307 |

| 30 Days Credit | -12 | -44 | -17 | 11 | 18 | 45 | 72 |

| 50% in 30 – 50% in 60 days | -12 | -44 | -75 | -48 | -41 | -14 | 14 |

| 60 Days Credit | -12 | -44 | -134 | -107 | -99 | -72 | -45 |

| 90 Days Credit | -12 | -44 | -134 | -225 | -217 | -190 | -163 |

Trader 1 demands mobilisations from all clients and so on day one of trading it commences business with a £117,500 in its account (inclusive of VAT). Trader 5 however does not receive payment until 90 days after supply (the last day of the month) or 120 days after Trader 1.

Trader 2 suppliers are on 30 days credit, Trader 3 trades 50% in 30 days and 50% in 60 days whilst Trader 4 trades on 60 days.

The cash balances of the businesses are shown in the chart below with Trader 1 having a cash balance at the end of month 6 of £307,000 which he can invest in the future growth of his business.

Conversely, Trader 5 still has a maximum overdraft requirement of £225,000 at the end of month three (18.75% of annual turnover), £163,000 overdraft at the end of month six and therefore it won’t be until month 15 that he finally gets into the black for the first time. Trader 1 however, will have a surplus cash balance of £480,000 at this point.

Click the image for a larger picture

Whilst many traders gear their business along the lines of Trader 2, they will put in place the bank facility and anticipate trading closer to Trader 3. The reality however is that if the Traders clients decided not to pay him until 90 days the trader will have a facility of £120,000, yet to pay all his bills on time would need an overdraft of £225,000. He will face additional costs of time and money in debt collection plus the inevitable dilemma of how to pay his bills and who to pay. He may be able to factor for additional cost, or even obtain more finance by offering security, but how many financiers will finance a debtor paying on 90 days when the contract states 30 days?

The ramifications can be extreme ranging from sleepless nights to the real danger of losing the business, not because a trader is any the less profitable than the others (they all make £240,000 per annum pre interest and tax profits) but purely because his clients refused to pay on time.

In the past many companies may have turned to their banks for financing or factoring companies but these same institutions will in turn look at the extended payment terms and conclude that the SME is a more risky enterprise and accordingly decline to extend the facility. A survey by the Bank of Scotland found that 68% of SME’s regularly suffered cash flow problems as a result of late payments.

We often read in the press that it is the bankers who are to blame for the slowness of SME’s pulling out of the recession due to their lack of willingness to lend to SME’s but it’s my strong believe that we are looking in the wrong direction. It’s not additional bank lending that SME’s need to pull out of a recession, it’s reduced payment periods to give SME’s resources to invest in new jobs, technology or develop new products etc.

As demonstrated by Unilever, good ‘corporate governance’ does not extend to its supply chain and if the EEC is serious about supporting SME’s through improved cash flow by shortening credit terms, then they must give SME’s the assistance through legislation. I suggest that the EEC should adopt a much tougher stance towards medium and large companies making individuals - and specifically finance directors - personally responsible through a series of fines coupled with a ‘name and shame’ scheme. Until this approach is taken, I believe growth and job creating within the SME sector will continue to be hindered.

Ashley Smith ACCA MICM

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.